Assessing Improvisation in Elementary General Music

For many music educators, improvisation can feel difficult to assess. Many of us view improvisation as a personal expression of musical ideas. We may think of it as subjective, instead of as a concrete “right or wrong” task.

In many ways, these views are accurate! Improvisation is a divergent activity, meaning there are multiple possible correct answers. It also necessitates personal musical choice, which can be subjective. These characteristics of improvisation are accurate, but that doesn’t necessarily take away from assessment validity. When we frame assessment as how we know what students need from us, clarify our goals with long-range planning, and collect data in a play-based way, we’re set up well to assess improvisation.

Let’s look at some specific ways to assess improvisation in an elementary general music setting.

We’ll start with the activities themselves, and then discuss principles to keep in mind when it’s time to improvise with student musicians.

You can find more detail about assessment for elementary general music in the assessment course.

Improvisation Assessment Examples:

Improvising a Loud and Quiet:¿Quién Es Esa Gente?

Sourced from Vamos a Cantar: 230 Latino and Hispanic Folk Songs to Sing, Read, and Play

In this example, Kindergarten students sing a loud or quiet improvisation, depending on the musical situation they’re describing.

Clarifying Goals through Long-Range Planning:

Loud and quiet is an early comparative Kindergarten students explore. Throughout the concept plan students make musical choices, and at the end of this concept plan from The Planning Binder in the 2020 - 2021 school year, students improvise a story with a loud or quiet voice.

Because the purpose of this assessment is loud and quiet, we’re not concerned with a specific toneset students should use, or the length of the improvisation. We’re only assessing their appropriate use of a loud and quiet singing voice improvisation.

Assessment Logistics:

Song: ¿Quién Es Esa Gente?

Objective: Students improvise with a loud or quiet singing voice

Assessment Activity: Students improvise with a loud or quiet singing voice

Data Collection: The teacher listens to students improvise with a loud or quiet singing voice to the class and with a partner.

Measurement Tool: Rubric with a description of the improvisation:

The student improvises with a loud or quiet singing voice

The student does not improvise with a loud or quiet singing voice, or does not improvise

Lesson Segment Time: 3 minutes

The Assessment Process:

Sing the song and pat the steady beat.

The teacher sings the questions: When is it a good time to use a quiet voice? When is it a good idea to use a loud voice? Please think your answer in your head, then get ready to sing it.

Students brainstorm ideas, then share their answers with a loud or a quiet improvised melody.

Examples:

“It’s a good idea to use a loud voice on the playground”

“It’s a good idea to use a loud voice at a birthday party”

“It’s a good idea to use a quiet voice in the library”

“It’s a good idea to use a quiet voice when my little brother is sleeping”

In between each sharing, students sing the song with a loud or quiet singing voice and motions to show loud and quiet.

Students turn to a partner and take turns sharing their ideas with a loud or quiet singing voice.

Data Interpretation:

We might look at the data and decide we’re ready to move onto the next musical concept! We might also look at the data and decide students would benefit from more practice with a loud and quiet singing voice. This part of the process is typically an intuitive understanding on the part of the teacher. As we collect the data (listen to students improvise) we normally have a clear sense of how to interpret the assessment results and how to adapt our next steps. We just might not always recognize that our intuitive redirection of the next activity is based on data analysis.

Improvising with Rhythmic Fluidity: Ickle Ockle

Sourced from Kodaly.hnu.edu

Game: Students walk in a circle holding hands and singing the song. At the end of the song, students find a partner (the partner may be anyone in the circle besides their immediate neighbor). Any student without a partner goes to the middle and the game begins again.

Clarifying Goals through Long-Range Planning

In this improvisation example, students improvise eight beats as a class and with a partner.

One of the characteristics of musical fluency is that students’ improvisations use a fluid, natural flow of music, without stopping and starting or disrupting the steady underlying pulse. Because the goal in this activity is rhythmic fluidity, it isn’t necessary for students to use a specific set of rhythms, or use part of their partner’s question material in their own improvisation answer. Any output with smooth pacing is an accomplishment of the goal.

Assessment Logistics

Song: Ickle Ockle

Objective: Students improvise eight beats with rhythmic fluency

Assessment activity: With a partner, students improvise eight beats with rhythmic fluency

Data collection: The teacher listens and watches students improvise with rhythmic fluency as a class and with a partner. Because the game is repeated more than once, the teacher has the opportunity to listen to multiple students in different parts of the classroom, paired with different improvisation partners.

Measurement Tool: Rubric with a description of the improvisation:

The student improvises with complete rhythmic fluency throughout the entire performance

The student improvises fluently throughout the majority of the improvisation. Some articulations may occur slightly behind or ahead of the steady beat.

The student improvises with inconsistent rhythmic fluency

The student does not improvise

Lesson Segment Length: 6 minutes

Previous Knowledge and Experience: Before this activity, students would have plenty of experience singing and playing the game to Ickle Ockle. They would also have cognitive knowledge of and diverse experiences (including improvisation) with the rhythms used in the song: ta, ta-di, and ta rest.

The Assessment Process:

Sing and play the game to Ickle Ockle as normal.

In the next round of the game, the teacher claps an improvised eight-beat rhythm. Students improvise their own eight-beat response back.

The teacher demonstrates sample improvisations with fluency (a consistent steady pulse underlying the improvisation) and without fluency (an inconsistent steady pulse underlying the improvisation). Students identify the use of a “smooth” or “jerky” steady beat in each example.

Sing and play the game again with the teacher improvising the rhythmic question and students improvising the rhythmic answer.

After a few rounds, and when the teacher observes that students are ready, students improvise both the question and the answer:

Sing the song and play the game. When students find their partner, one claps an eight-beat question and the other claps an eight-beat improvised answer.

Data Interpretation

When we look at the data from the activity, we might decide we should go back and practice improvisation in other structures before asking students to improvise in pairs. We might also decide students should repeat the activity in the next class, but perform their improvisations as solos. Depending on our pedagogical goals, we could also determine that students are ready to move from clapping their improvisations to playing them on barred instruments in question and answer form. The way we interpret and apply the data will go back to our long-range plans for student learning.

Improvising with Takadimi: Old Brass Wagon

Source: Hamilton, G. M. (1914). The Play-Party in Northeast Missouri. The Journal of American Folklore,

27(105), 289–303. https://doi.org/10.2307/534622

Clarifying Goals through Long-Range Planning

In this improvisation activity, students are asked to use a specific rhythm in their improvisation. In this specific case, the inclusion of takadimi is the only quantitative measurement of the improvisation we need. We might notice other important elements of the student’s improvisation, such as their level of rhythmic “flow” (fluency) or the length of the improvisation. We might even document those observations so we can alter the next class activities. However, those performance data would not factor in to the assessment evaluation for this specific improvisation experience. In this case, we are only assessing students’ use of the rhythmic element, takadimi.

Assessment Logistics

Song: Old Brass Wagon

Objective: Students improvise with takadimi

Assessment Activity: Students improvise with takadimi

Data Collection: The teacher listens to students improvise with takadimi, and students self-assess their improvisation

Measurement Tool: Rubric with a description of the improvisation:

The student uses takadimi in their improvisation

The student does not use takadimi in their improvisation, or does not improvise

Lesson Segment Time: 10 minutes

Previous Knowledge and Experience: Before this activity, students would have plenty of experience singing and playing the game to Old Brass Wagon. They would also have cognitive knowledge of and diverse experiences with the rhythms used in the first three phrases of the song: ta, ta-di, and takadimi.

The Assessment Process:

Students sing and play the game to Old Brass Wagon.

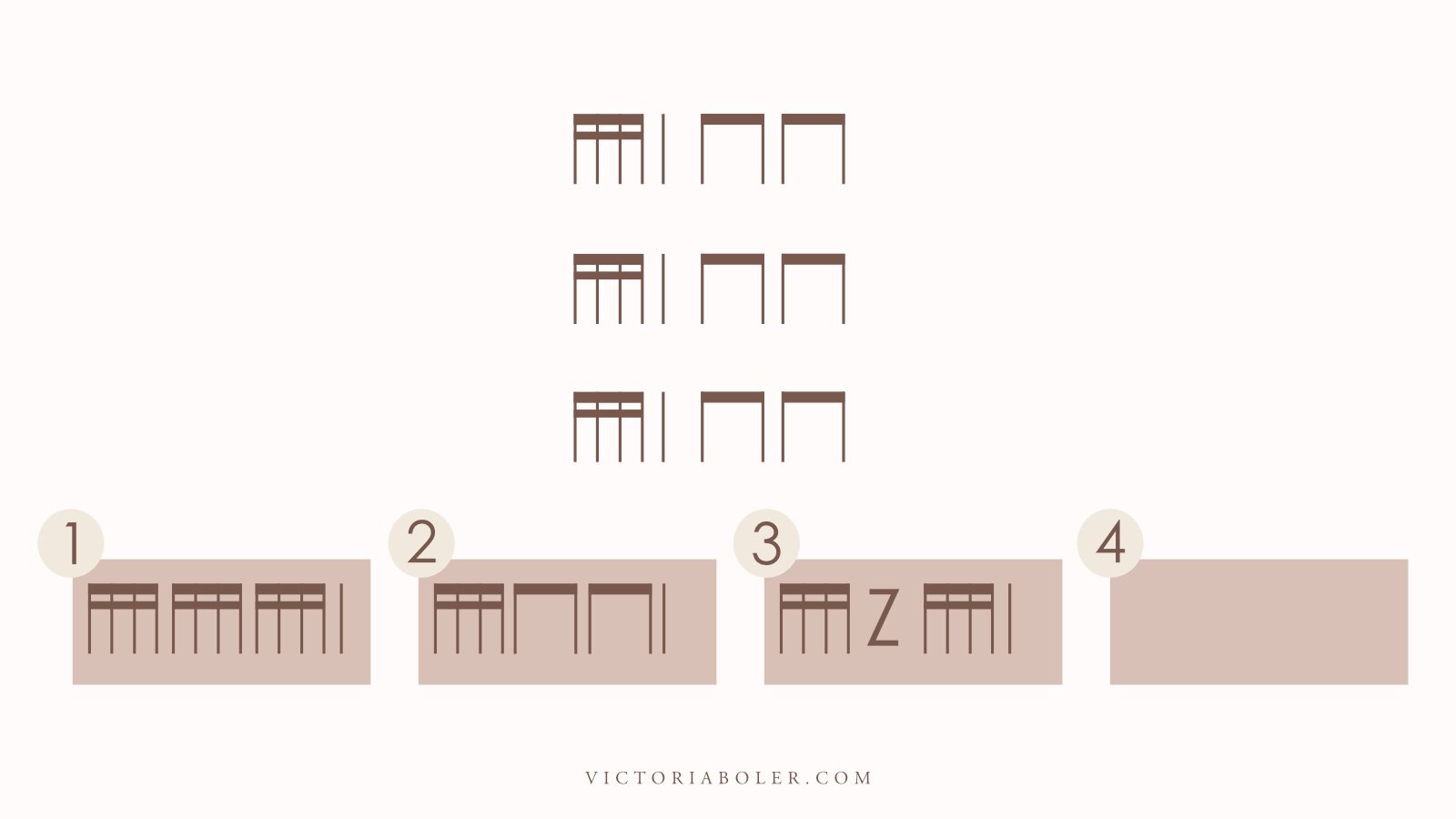

Show the notation of the song on the board with different song endings. (These endings might be some the teacher provides ahead of time, or students might suggest them as a part of the lesson process.)

Seated, students play the rhythms on the board with their choice of body percussion. Try out the first three notated endings.

Notice that the fourth ending is empty! Tell students this box is empty so they may make up their own rhythms instead of reading what the board says to do.

Students choose their favorite ending (including improvisation), hold up their fingers to show their choice, and tell someone next to them which one they’ll choose to play.

Pat and clap the rhythm of the song again. Students play their chosen ending.

This time, let’s stand up and everyone will improvise their own rhythmic ending. We’ll do this two times. The first time, you’ll improvise whatever you want! The second time, you’ll do your best to include “takadimi” in your response.

Students turn to a partner and explain the directions (the first time, just improvise. The second time, improvise using takadimi).

Pat and clap the rhythm of the song two times.

Nice! Did you include takadimi in your improvisation? Students show a thumbs up / thumbs down, or sign language for yes or no.

Data Interpretation

This activity gives students many opportunities for musical choice. In the convergent part of the process when students read the notation, they choose the body percussion they’ll use. When it’s time to improvise, they’ve had multiple examples of endings that use takadimi. They also have the opportunity to try out their improvisation before consciously trying to use takadimi in the ending. When we observe these many scaffolds of musical choice, improvisation, and conscious musical knowledge, we’re gathering important data that we can use in future instruction.

Each step in the process gives us important data about how students are handling varied opportunities for musical choice. When we look at the data for the improvisation assessment, we might decide we’re ready for longer improvisation activities, like eight or sixteen beats. We might also use qualitative data to observe that students struggle to read the rhythmic notation on the board accurately. In that case, we might review aural skills and visual notation of takadimi in the next lesson.

Adapting Prior to Notation

If students do not yet have conscious knowledge of takadimi, the activity can be adapted with text and graphic notation instead of Standard Western notation. Use the words, circle to the, wagon, and left.

We’ve looked at three examples of assessing student improvisations.

Let’s zoom out and discuss principles to keep in mind when it’s time to assess improvisation in elementary general music.

We’ll start with looking at what exactly improvisation and assessment are.

We’ll also talk about the types of data we can use to assess improvisation.

Last, we’ll look at the role of long-range planning in the improvisation assessment process.

Defining Improvisation and Assessment

Sometimes the reason we feel confused about how to assess improvisation is that we lack clarity in what improvisation is, and what assessment is.

Improvisation:

When students make a musical choice and perform it spontaneously, they are improvising. This spontaneous musical choice might be as simple as making up new motions on the spot to go with a song or as complex as improvising over a 12-bar blues progression.

The simultaneous imagination and production of a sound is key in setting improvisation apart from other musical processes. In contrast, creative tasks like arranging and composition involve space between the time it takes to have a musical thought and the time it takes to execute a musical thought. Improvisations are also complete works in and of themselves. The creator doesn’t intend to go back and edit them later, as is the case with composition and arranging. Improvisations exist in the moment they are produced.

Assessment:

Assessments are how we know what students need from us next. Assessments are collaborative and intentional musical experiences where we design a learning experience and get feedback from students so we can craft the next learning experience.

Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment Data for Improvisation

Assessment data might take the form of numbers and letters to be used as grades, numbers and letters that aren’t used as grades, or qualitative observations like sticky notes.

These data can be divided into two categories:

Qualitative: Data that narrate or describe characteristics

Quantitative: Data that show quick summarizations with an absolute value (like numbers or letter grades)

Both of these forms have their pros and cons, and both forms of data can be useful to us in different ways.

When we assess improvisation we may choose to document quantitative data with a quick numerical score, but make a note to ourselves using qualitative data so we get more background information about the student performance.

Assessing Improvisation: Clarify Goals through Long-Range Planning

Assessment of improvisation is directly tied to long-range planning because the assessment is directly tied to the purpose of the activity.

The assessment practice we choose will be dependent upon our goals for the improvisation itself. These goals are directed by the larger curriculum planning process for our program as a whole.

When we craft our value statement for our program at the beginning of the curriculum planning process, we might include values-based ideas such as wanting to develop musical thinkers who can actualize their ideas.

For the purpose of assessing improvisation, its helpful to be much more narrow with goals, and clarify the specific pedagogical outcome we want to observe.

Long-Range Planning and Improvisation Assessment:

Our long-range plans frame the activities we do in the music room. When we plan this way, we’re not planning from activity to activity. Instead, we’re choosing strategic learning experiences that build off of each other so students build knowledge through active musicking. Each activity we choose serves the larger learning goal, as we’ve articulated in our long-range plans.

Depending on our long-range plans, we might have specific goals that are based around another musical concept (for example - rhythm, pitch, or form), or another mode of musical expression (for example - improvising on barred instruments or recorder).

Sample Improvisation Goals:

Here are some sample goals we might articulate when it’s time to improvise. Notice each of these goals is an outcome we can hear and see.

Improvise 8 beats

Improvise with fluency

Improvise in question and answer form

Improvise within a specific toneset or rhythmic set

Improvise with speech

Improvise in a head voice

Improvise with a clear recorder tone

Clarity Through What We Don’t Assess

When we clarify our long-range goals, we know what we care about assessing. Equally important, we know what we’re not assessing.

For example, if our primary objective is for students to improvise for eight beats, that is the only thing we’re assessing. In that improvisation, we’re not concerned with the tone they produce on the instrument, how expressive the melodic line is, or whether or not they used question and answer form. There may be things we notice about their improvisation regarding the tone, expressivity, or form. However, because it’s not the purpose of the assessment, it’s not something we’ll document.

Assessing Improvisation in Elementary General Music

Today we’ve looked at several examples of assessing improvisation in elementary general music.

There are many more possibilities to framing assessment in elementary general music, but the principles will stay the same, regardless of the form the assessment takes.

We’ll start with what exactly improvisation and assessment are.

We’ll determine the type of data we’ll use to assess improvisation.

Last, we’ll ground the assessment in long-range planning.