Curriculum Maps for Elementary General Music

“What will I teach this year?”

“What grade does this song work for?”

“What do I do after this unit?”

These are questions we all ask in our teaching, and we can start to explore their answers with a curriculum outline, or curriculum map.

A curriculum outline is one document that can make our planning time both manageable and meaningful.

Today we’ll:

Look at a curriculum outline example

Talk about how it’s constructed

Look at other possible sequences

Think about what’s missing in the document

Let’s jump in!

Curriculum Outline

Here is an example of the curriculum outline from The Planning Binder 2023 - 2024 school year.

This is a broad look at an entire elementary music program, at each grade level.

This document is organized by musical concepts. The emphasis is on foundational musical elements that can be transferred to many different musical skills and many different areas of musical understanding.

Two important items to consider in the interpretation of this document have to do with the role of discipline concepts and the distinction between experiences and conscious learning.

Organized By Discipline-Specific Concepts

As we organize our curricula by concepts, we help students build understanding and transfer it to new musical situations, both inside and outside the classroom.

For example, if we teach students to understand pitch - melodic contour, intervallic relationships, etc. - and we give students tools to listen critically, analyze what they hear, and articulate their thinking, they have what they need to transfer their understanding to many different musical scenarios.

They are equipped to play a melody by ear on guitar or harmonica or metallophone. They might choose to compose their own melody and teach it to a friend or arrange it for an ensemble.

In the construction of this curriculum outline, there is a choice to lean toward transferrable musical patterns and ideas and lean away from siloed musical units.

Experiences and Conscious Vocabulary

Another thing I think is important to note about this document is that these are times when the musical ideas are highlighted and students are aligned on musical vocabulary.

These are not the only times the musical events are experienced.

For example, we can sing songs in many different modes (like these entrance songs) even if students do not consciously know the mode’s label and how to aurally identify it or write it on the five-line staff.

Teaching Sequences for Elementary Music

In our conversations about what we’re going to teach in the next lesson, the “why” behind a musical sequence can sometimes be overlooked.

Even though it’s easy for all of us to get caught up in our efforts to make music with students as quickly and efficiently as possible, thinking through the purpose of a teaching sequence can be helpful as we make decisions about our own situations.

Known to the Unknown

One of the core principles we use in a spiraled curriculum is the idea of moving from the known to the unknown.

This came out of the work and followers of Pestalozzi. Educators who use this principle believe that learning does not take place in a vacuum. When students learn something new, it is because they have connected it to previously known material.

Musical knowledge and understanding are predicated on older information and experiences.

As we move from what Pestalozzi described as “from the simple to the complex,” we can help students process through and link old (known) musical patterns and vocabulary to new (unknown) musical experiences. Students can consider the aural qualities of new musical material (tonality, duration, intervals, patterns, etc.) by comparing it to the musical qualities they already know.

Sequence Options

As we put together a sequence of musical patterns, we want the information to be in a logical and artistic flow of musical ideas.

The way we get there is by choosing a sequence that has patterns organically represented in the repertoire. The role of the teacher is not to manufacture a curricular experience. Instead, it is to help students guide their ears and pull out extractable patterns.

With the criteria of a logical and artistic flow of patterns represented organically in the repertoire, there are many possible options for musical sequences! And music teachers certainly use a variety of well-thought out progressions of musical ideas in our teaching. Teachers naturally use different sequences, and even within classrooms following the same sequence, no two teachers give instruction or direct learning in exactly the same way.

Each situation is unique.

Example Sequences

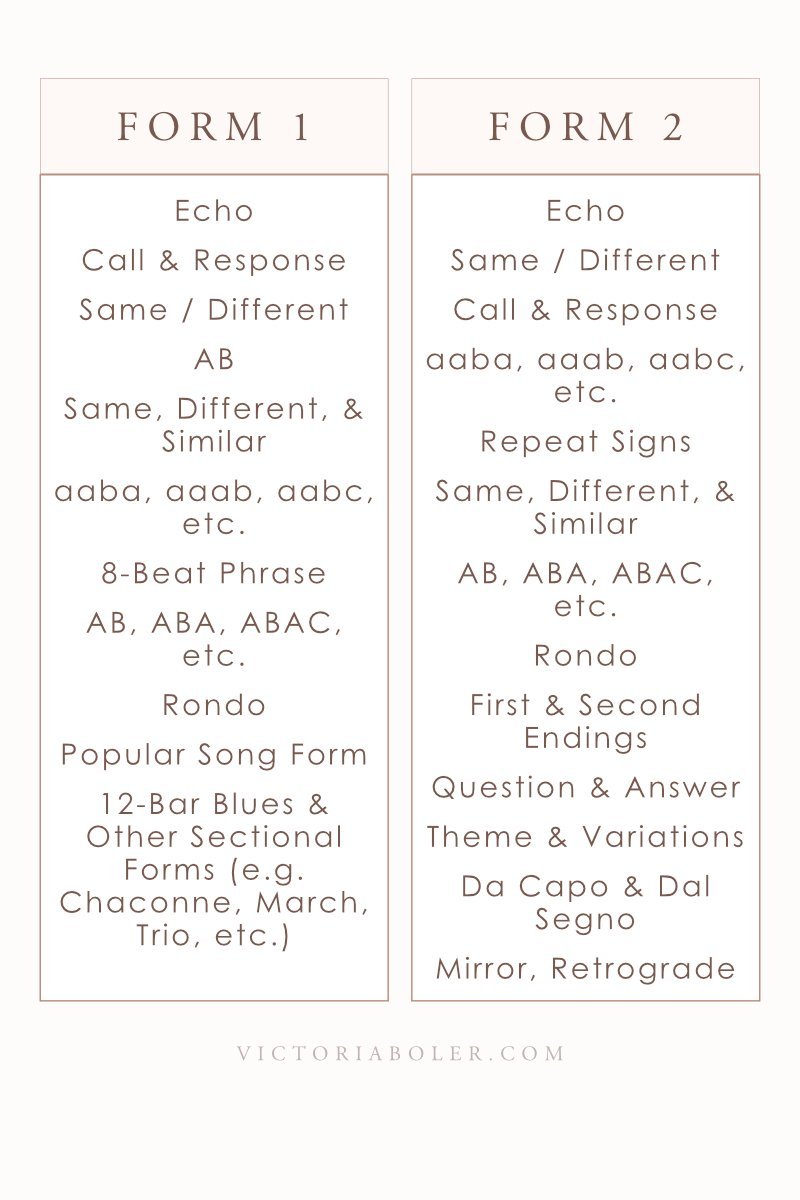

Here are a few example sequences for elementary general music. Certainly, more exist in our classrooms, and even more exist in musical repertoire.

The reason to consider these examples is to illustrate that each of us can make informed decisions about our progressions based on many different factors.

A list of sources is included at the bottom of this post.

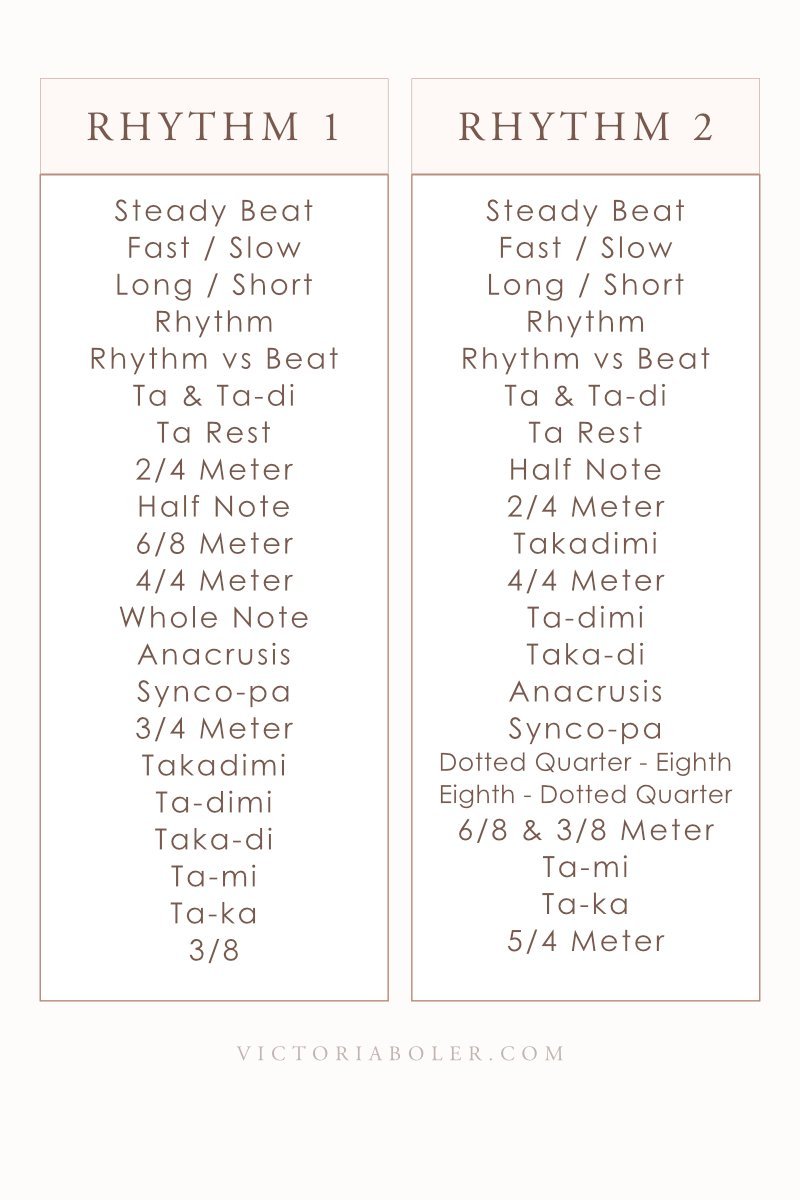

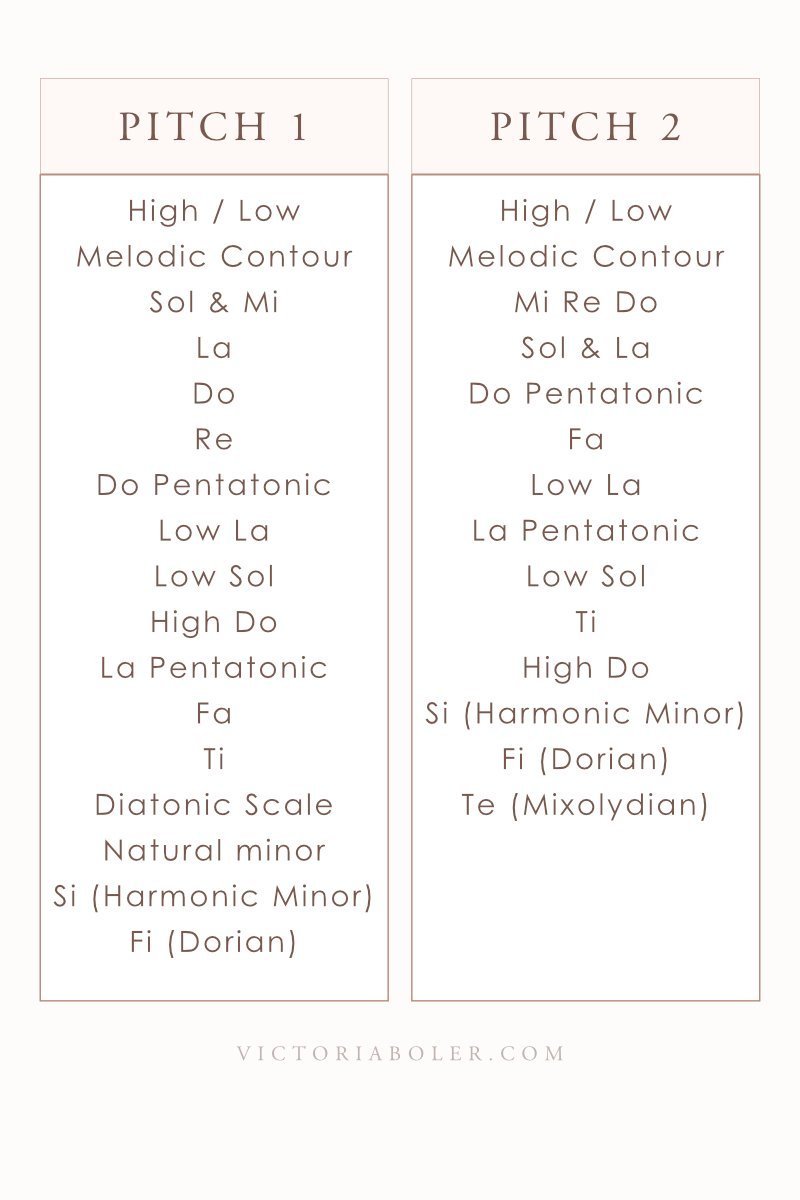

Rhythm and Pitch Sequences

Many educators choose to structure their curricula largely around rhythm and pitch.

In my opinion, this is because having aural training and common vocabulary around rhythm and pitch allows us to communicate more clearly about other musical elements.

So for example, we can describe the form of a song easier if we can describe the rhythm changes in the different sections. It’s easier for us to describe the harmonic outline of a piece if we have training and a common vocabulary to describe the contour of the bass line.

In this decision of a curriculum outline, rhythm and pitch function as pillar progressions, and do a lot of heavy lifting in the framing of other elements.

Here are a few examples - to reiterate, there are more options available than what is represented here!

Form, Texture & Harmony

Other musical elements, such as form, texture, harmony, dynamics, etc., also arise organically from the repertoire.

However, we typically don’t see curricula grounded on these elements in the way we see them oriented around rhythm and tonal patterns.

Additionally, many of these micro-concepts arise as students are ready for them from a skills-based perspective. There is a natural physical, cognitive, and aural level readiness students work through on their way to things like arpeggiated borduns and parallel harmony.

Which One Should I Use?

Because each of these sequences is a skillfully-crafted progression of micro-concepts that are naturally represented in the repertoire, how might we go about choosing one to use?

I prefer the one we’re using inside The Planning Binder, but the good news is that rarely will we find ourselves stuck with one set of sequences we find on a website or in a textbook.

Year to year, school to school, and perhaps within a single semester, we can pivot and make adjustments based on what will work best for our students. Though consistency in the sequence overall will improve cohesive learning, we are largely free to adjust our focus based on student feedback.

Listen to Dr. Amanda Hoke talk about changing her melodic sequence in tomorrow’s podcast episode.

Considering a few options gives us a sense of the menu we have when looking for a spiraled progression of concepts for our programs.

Implications of a Sequence

Ultimately, that is one of the big implications for a teaching sequence.

The progression we choose will impact the repertoire we select.

The dance is also true in reverse: the repertoire we select will impact the sequence we choose.

With this lens, when we come across a fun activity we want to try, the question is not, “What grade is this song for?” The question instead becomes, “What previous knowledge or interaction is this song experience predicated on?”

What’s Missing Here?

There are many things missing from a curriculum outline like the one in this post!

Musical Content

From a content standpoint, there are plenty of concepts that exist in music that aren’t listed here at all! Music is a big subject to tackle and it extends far outside this document.

Howard Gardner commented that “the enemy of understanding is coverage,” and I think that is helpful here. By necessity, and for the sake of prioritizing understanding over coverage, we choose to consciously interact with some elements and not with others.

Musical Pedagogy

The other thing is when we start to think about what this document might look like in our classrooms, it becomes very obvious that there are a lot of things missing here in terms of musical actions.

This document tells us what students are learning, broadly speaking, but it doesn’t tell us what students are doing with this information. This gives us the content, not the instruction. We know we’re going to go far beyond reading and writing with these patterns and concepts, but that isn’t reflected here.

With each concept, there are so many ways we could actualize our knowledge with musical skills, and many different dimensions of social interactions and connections. We could also add things like enduring understandings or macro concepts or how we’ll show our learning with an authentic performance assessment. The opportunities for rich, lived, classroom experiences and curricular lenses are functionally endless.

What is Curriculum?

We tend to weave together a lot of things when we use the word, “curriculum.” Wiggins and McTighe talked about the Latin roots of the word “the course to be run.” Colleen Conway also talked about curriculum as being so much more than a document - we’re talking about what is taught, what is learned, and how we will move students through the learning process.

This document is limited on purpose.

It gives us a big picture of how musical concepts are spiraled throughout the program. In my opinion, it’s extremely useful because it gives us a way to streamline our decisions, that way we’re not stuck looking for fun activities to fill time in our lesson planning. The activities can lead to something that we know is leading to something else.

- Sources -

How to cite this article

Boler, V. (2023, July 9). Curriculum map for elementary general music. Victoria Boler.

Sources

I learned about the construction of this document from a music teacher named Mrs. Rogers when I was in my undergrad. Thank you, Mrs. Rogers!

Benedict, C. (2016). "Reading" Methods. In C. R. Abril & B. M. Gault (Eds.), Teaching general music: Approaches, issues, and viewpoints (pp. 347–367). essay, Oxford University Press.

Brandt, R. (1993). On teaching for understanding: A conversation with Howard Gardner. ASCD. Retrieved November 2022, from https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/on-teaching-for-understanding-a-conversation-with-howard-gardner

Bruner, J. (1960). The process of education. Harvard University Press.

Conway, C. (2015). Defining Musicianship-Focused Curriculum and Assessment. In Musicianship-focused curriculum and assessment (pp. 3–21). essay, GIA Publications, Inc.

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Music Sequence Sources

Brumfield, S. (2012). First, we sing! Hal Leonard Corporation.

Eisen, A., & Robertson, L. (2005). Directions to literacy, teaching the older beginner: A teacher's guide to introducing music to the older beginner. Sneaky Snake Publications, LLC.

Eisen, A., & Robertson, L. (2009). Yearly plans: For coordinated use with an American methodology. Sneaky Snake Publications.

Eisen, A., & Robertson, L. (2010). An American Methodology: An inclusive approach to musical literacy. Sneaky Snake Publications.

Frazee, J. (2006). Orff Schulwerk today: Nurturing musical expression and understanding. Schott Music Corp.

Frazee, J. (2012). Artful - playful - mindful: A new Orff-Schulwerk curriculum for music making and music thinking. Schott.

Frazee, J., & Kreuter, K. (1997). Discovering Orff: A curriculum for music teachers. Schott.

Goodkin, D. (2013). Play, sing, & dance: An introduction to Orff Schulwerk. Schott.

Houlahan, M., & Tacka, P. (2015). Kodály today: A cognitive approach to elementary music education. Oxford University Press.

Klinger, R. (2014). Lesson planning in a Kodály setting: A guide for music teachers. Organization of American Kodály Educators.

Peek, Aimee Noelle, "A Comparison of the Kodály Methodology and Feierabend's Conversational Solfege" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 27.

Rappaport, J. (2000). The Kodály teaching weave. Bel Canto Press.

Sams, R., & Hepburn, B. A. (2015). Purposeful pathways: Possibilities for the elementary music classroom. Music is Elementary.

Steen, A. (1992). Exploring Orff: A teacher's guide. Schott.