Sound Before Sight in Elementary General Music

Music is an aural artform.

The notation is a way to preserve the sounds, but the notation of the music is not the music.

How can we teach elementary general music in a way that centers music as an aural artform, and focuses on hearing and understanding?

What is Sound Before Sight?

“Sound before sight,” or “sound before symbol,” or “sound-to-symbol” teaching is a principle many music education approaches follow, such as Orff Schulwerk, the Kodaly Concept, Music Learning Theory, Suzuki, and Feierabend.

With a sound before sight approach, we begin learning music through participatory interactions (listening, singing, speaking, playing, and moving) before we introduce visual notation and classroom vocabulary.

When notation is introduced, students have already built the meaning of the notation through experiences.

Learning Music Like a Language

Sound before sight is the way students learn to read a language, and while music is not a language, we can learn it the same way.

When a child is learning how to read, they have many years of experience just hearing language all around them. They also have years of speaking, and having interactive conversations in that language. When it is time for children to learn to read and write, they have an aural and oral context for the written language.

Imagine if we had children wait to speak until they could read and write. Imagine if children were only allowed to speak and have conversations using words they could read and write orthographically.

In the same way, we want young musicians to have time to interact with the aural and oral transmission of music in a true way before we add an unknown visual. We can use the sound before sight approach to emphasize musical experiences that lay a foundation for notational literacy.

Learning to hear vs to read: Is Sound Before SIght still Relevant?

To me, there’s something magical in sound-before-sight which I think makes it highly relevant in today’s music programs: this approach is much more about learning how to hear rather than learning how to read.

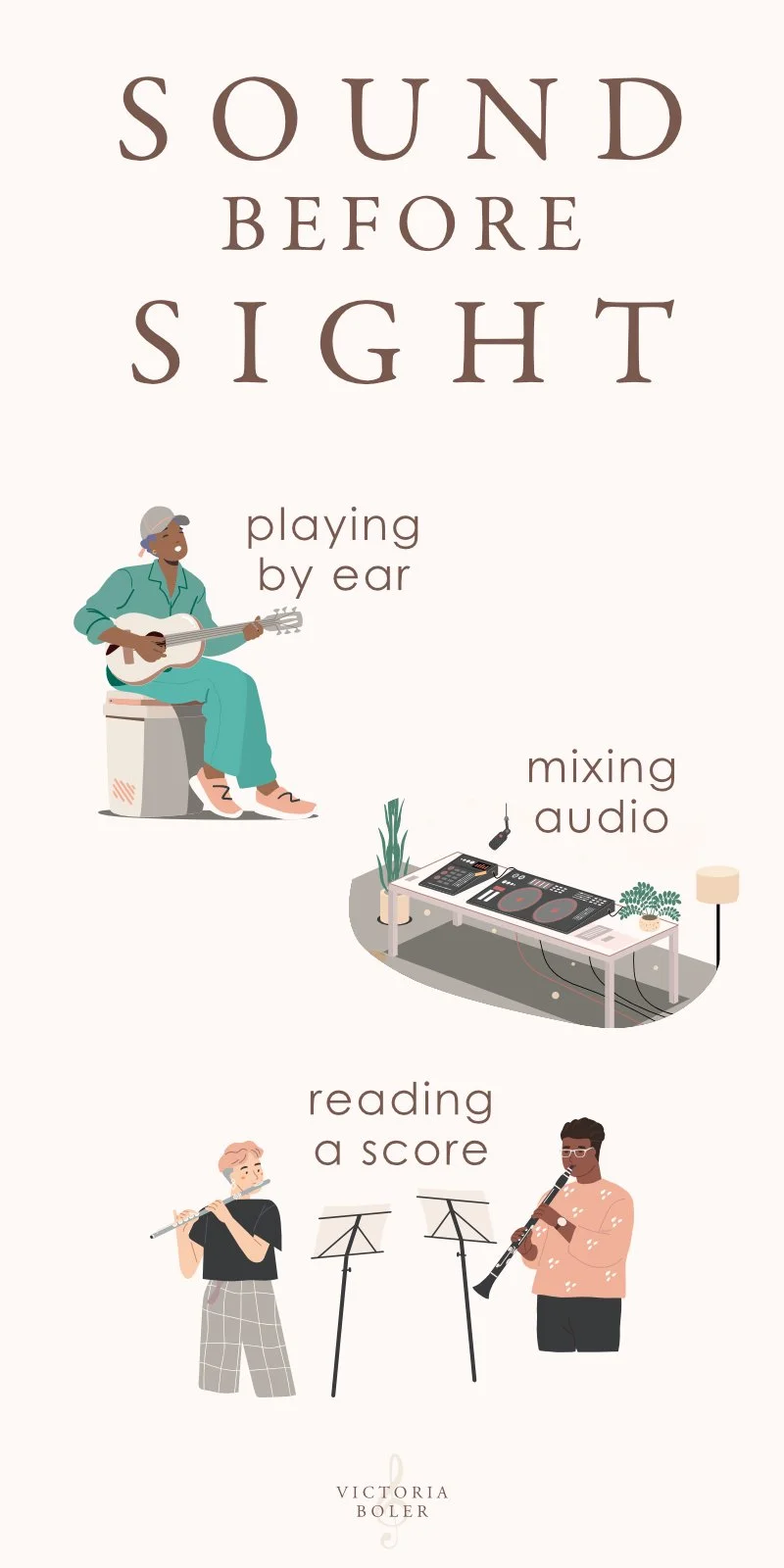

The emphasis is on developing students’ aural skills, which will serve them well in any field of music. Regardless of which musical pathway students end up on outside of class, the ear training as the foundation of the sound-to-sight approach will be useful.

When students engage in something like informal learning processes, they’ve developed the aural discrimination to hear a song and learn it by ear, or read a chord chart. If they go on to be an audio mixer, they’ve honed their aural sensitivity to specific musical qualities of each track. If they go on to be an instrumentalist playing a film score reading standardized Western notation, they have the aural training and a way to mentally link the aural event to a visual representation.

To me, this approach is highly useful and very relevant because it develops aural skills and analytical thinking that students can employ in any field of musicing.

Pestalozzi and Sound Before Sight

The importance of a “sound before sight” approach was developed through the work and followers of Heinrich Pestalozzi. Pestalozzi was a Swiss educator in the 18th and 19th century. He believed in the importance of experiences and sensory-based learning, called Anschauung.

In music education, our use of this principle has evolved from its early use in American public schools which focused primarily on singing and vocal development as the entirety of the school music program.

Today Pestalozzi’s principle continues to be applied differently in music programs with music education approaches such as the Kodaly concept, Orff Schulwerk, and Music Learning Theory.

Sound Before Sight Examples:

Experience First

Pestalozzi advocated that children should learn through direct, concrete experiences. This experiential education focused on “Anschauung,” or sense intuition, and learning through observation, exploration, and hands-on activities.

In this constructivist model, the student is an active participant in their own learning, as opposed to a passive participant who receives information from the teacher.

What Does Experience First Look Like in Music Education?

In practice, we can think of sound before sight as actually active experience before sight.

In this approach to teaching and learning music, we center learning experiences around active musicking. That is, active involvement in musical tasks like singing songs, speaking rhymes, playing games, playing instruments, and moving.

The way to learn music is through musicking - embodying musical experiences. Musical comprehension is built in an active embodied experiential context.

When it’s time to actually pull musical knowledge from these experiences, we need a place for the melodic or rhythmic or form or textural understanding to live aurally.

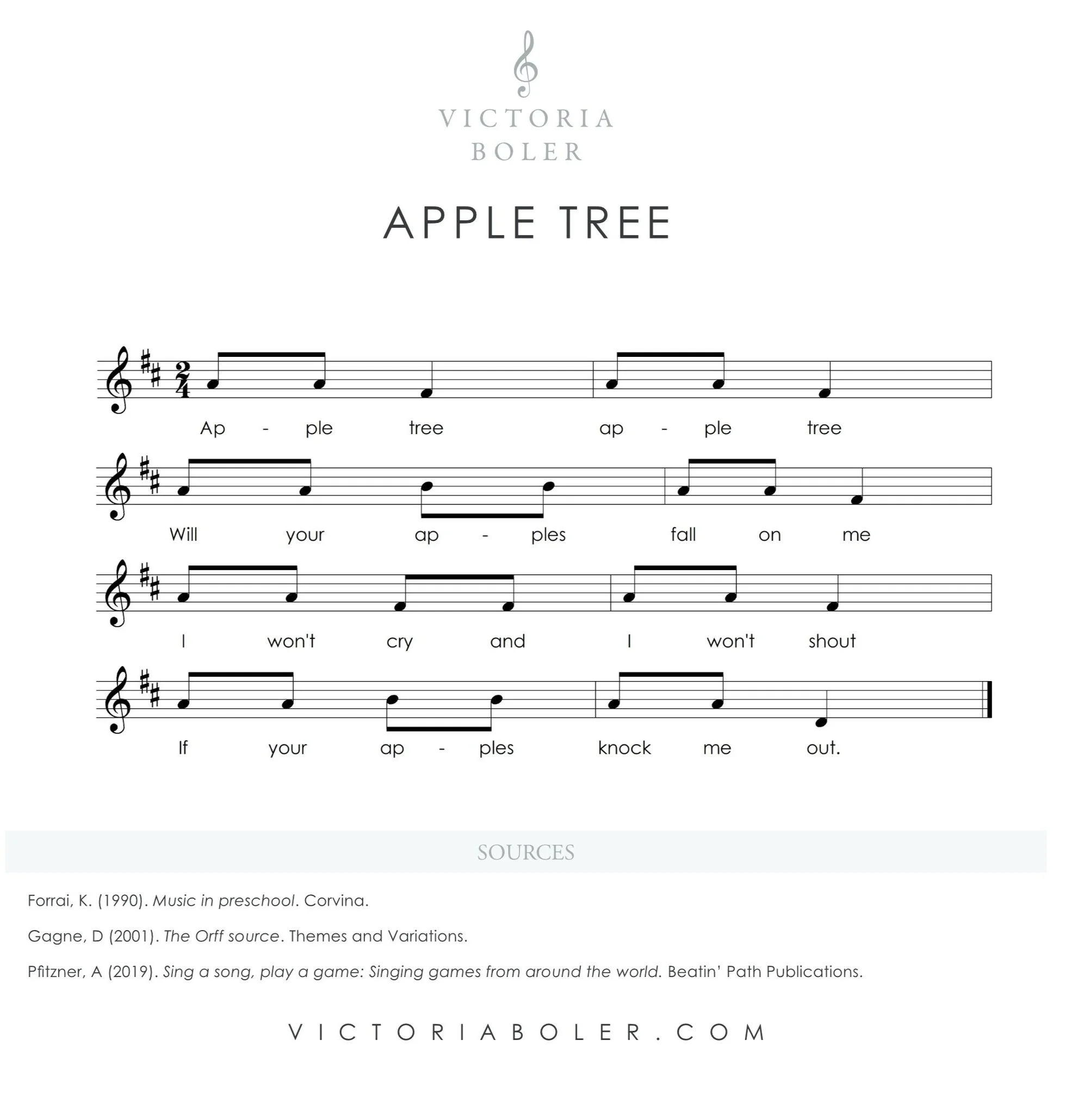

Experience Example 1: Apple Tree Game

This is one application out of many possible uses of sound before sight: let’s imagine that in 1st grade we want to teach a tritonic melody, in this case sol, la, mi.

Instead, we’re going to start with an active experience - in this case, a singing game.

Directions:

There are many different versions of this singing game!

In the one I use, two students connect their hands above their heads to create a tree. The rest of the class walks in a circle under the tree while they sing the song.

At the end of the song, the players creating the tree lower their branches and capture one student. That student becomes an additional tree with the teacher and the game begins again. Each round of the game creates more and more trees.

Experience Example 2: Vocal Improvisation

We can also use improvised singing conversations to experience sol, la, mi without using those names.

Singing the question with a sol, la, mi melody, we’ll ask students what they would do with all the apples that fell from the tree.

Students sing their responses back with a sol, la, mi toneset. Examples might be, “I would take them to my grandma,” or “I would share them with you,” or “I would peel them,” etc.

At this point in the teaching and learning process, students are using the toneset to sing, move, and improvise. Our emphasis is on creating contextual musical experiences.

Sound Before Sight Examples:

Known to the Unknown

Interconnected to the idea of experiencing first, another central belief from Pestalozzi that we use today is moving from the known to the unknown. Pestalozzi believed that Anschauung needed to be experienced before the key word in the lesson was used.

Moving from the concrete to the abstract, and the familiar to the unfamiliar, learning begins with an existing set of knowledge and experiences. We use those existing sets of knowledge and skills to make comparisons and connections to new things we encounter. We use our known informational landscape to investigate an unknown element.

What Does Known to Unknown Look Like in Music Education?

We want student musicians to link known musical concepts to new musical sounds.

Using this strategy of known to the unknown, students figure out new rhythmic and melodic elements by first categorizing them into what they are not. Does the melody go higher than the pitches we know? How much higher? How much lower? We can hear that a piece of melodic information is missing because we compare the new sounds to known sounds.

The sequence we use becomes the set of known musical concepts students will compare new musical sounds to.

Learn more about a Scope & Sequence for elementary music here

Known to Unknown Example 1: Aural Decoding

Let’s imagine we want students to aurally identify a new pitch higher than their known pitches, sol and mi. This is where we will link the new sound (la) to the known sounds (sol and mi) and where our musical sequence is so useful.

Sing the song and play the game to Apple Tree

Standing still, sing the first four beats on a neutral syllable while “painting” the melody (tracing the melodic contour in the air)

The teacher sings the question with a sol mi toneset: Those sound like pitches we know. In this class, what do we call them? (sol and mi)

Sing the first four beats on solfege with body solfege signs or Curwen hands signs

Sing the next set of four beats on a neutral syllable while “painting” the melody

Were all of those pitches sol and mi? (no) What was different about that melody? (answers may be divergent - the melody went higher)

Sing the first eight beats on a combination of solfege and a word students choose to describe the new pitch, like “up,” “sky,” etc.

Sol sol mi, sol sol mi, sol sol up up sol sol mi

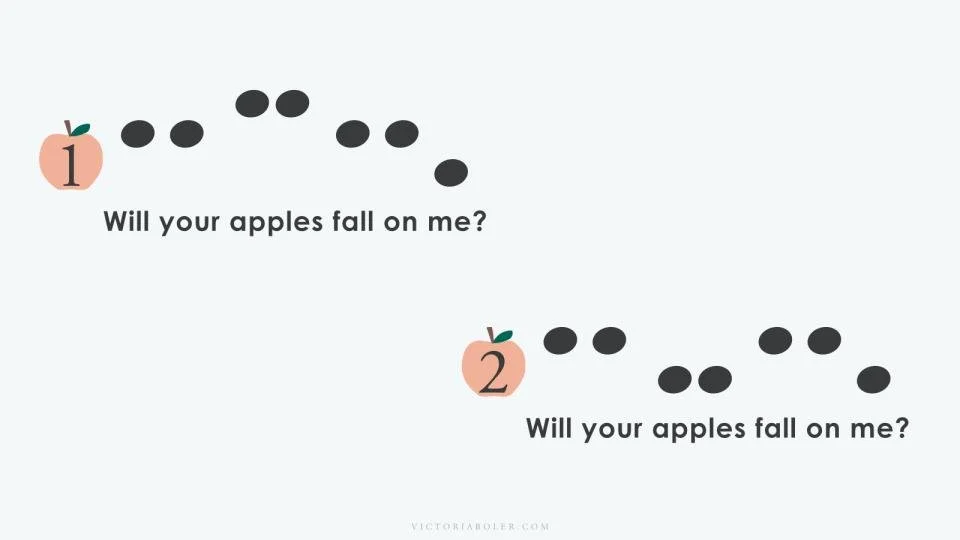

Known to Unknown Example 1: VIsual Representation

Students have analyzed the melody and found a new high pitch in the phrase.

At this point they might link the new sound to a visual representation of the sound.

Looking at the board, students work with a shoulder partner to decide which image shows the melody most accurately. Students show their answer by holding up a 1 or a 2, then turn to a shoulder partner and discuss their answer.

Other Ways to Visually Represent a Melody

There are so many more options for visually representing a melody in a sound-to-sight model!

Here are a few extras to consider….

Students can trace the melodic contour in the air. (They’ll do this without the teacher’s assistance.)

Students can place manipulatives like small erasers or Lego blocks to show the melodic contour on the floor in front of them.

Students can use a pencil to write the melodic phrase above the words of the text in an exit ticket. (When I do this, I also like to ask students why they chose to write the melody the way they did.)

Students can help the teacher or another student drag the target pitch higher or lower on the board by pointing up or down. Here are a few examples of what that can look like with la, do, and re:

After these interactions, students have (1) used the new pitch in a singing game (2) improvised with the new pitch (3) aurally identified the new pitch, and (4) notated the new pitch.

When the teacher introduces the classroom vocabulary for the new pitch, la, and how to write it on the staff, students have already constructed what the new solfege pitch means in a melody.

Sound Before Sight in Music Education

This experiential process allows students to connect musical components like melodies, rhythms, and dynamics with their existing auditory experiences. As a result, students develop a solid foundation in aural skills because they internalize music before they encounter its visual symbols. Whether those symbols are in the form of chord charts, tablature, the Nashville Number System, or standardized Western notation, sound before sight helps students interpret notation meaningfully when the time comes.